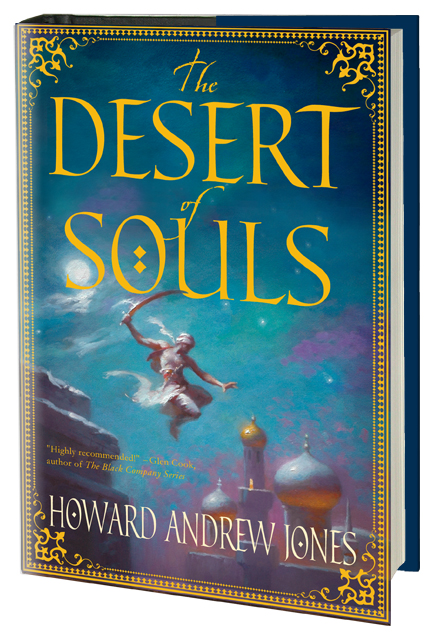

As I’ve noted in past interviews, 2011 is looking like a boom year for fantasy—and not only in the “urban” and “epic” tradition of fantasy. This month, Howard Andrew Jones has published The Desert of Souls, a historical sword-and-sorcery debut novel set in eighth-century Baghdad. Jones promises a sweeping adventure, pitting his scholarly Dabir and martial Asim against murderers, Greek spies, and a search for the lost city of Ubar—the Atlantis of the sands.

The adventures of Dabir and Asim have appeared in Jones’s short stories for the past ten years in publications such as Jim Baen’s Universe and Paradox. In addition to writing short stories, Jones has served as the managing editor of Black Gate magazine since 2004. In the below interview, Howard shares his thoughts on his debut, literary inspirations, and writing and editing.

Blake Charlton: Howard, welcome and thank you for taking the time to chat.

Howard Jones: Thank you for the invitation. It’s a true pleasure to be here.

To get the ball rolling, I always like to hear how authors think of their work. How would you describe Desert of Souls in your own words?

The blurb writer for The Desert of Souls actually did a far better job succinctly describing the plot than I’ve ever managed. Black Gate’s John O’Neill once said it’s like Sherlock Holmes crossed with The Arabian Nights except Watson has a sword, which is pretty apt, although the novel’s as much an adventure as a mystery. I think if you combine that description with Kevin J. Anderson’s blurb calling it “a cross between Sindad and Indiana Jones” you get pretty close to the feel.

It’s an origin story of how Asim and Dabir come to trust and rely upon one another to face a terrible evil. Things start small, with the discovery of a peculiar golden tablet that they’re charged with investigating, but before long they’re swept up into a dark plot that threatens not just Baghdad, but the entire caliphate. Sorcery, necromancy, sinister secrets, djinn, swordplay, they’re all in there, along with the requisite villain, who has legitimate grievances, and the clever Sabirah, who I couldn’t help but fall in love with a little myself.

It’s an origin story of how Asim and Dabir come to trust and rely upon one another to face a terrible evil. Things start small, with the discovery of a peculiar golden tablet that they’re charged with investigating, but before long they’re swept up into a dark plot that threatens not just Baghdad, but the entire caliphate. Sorcery, necromancy, sinister secrets, djinn, swordplay, they’re all in there, along with the requisite villain, who has legitimate grievances, and the clever Sabirah, who I couldn’t help but fall in love with a little myself.

What first inspired you to write a historical fantasy set in eighth-century Baghdad?

Neil Gaiman and P. Craig Russell took me to ancient Baghdad in issue #50 of The Sandman (“Ramadan”), but it didn’t occur to me until years later that I could take anyone there myself. I know a lot of my choice stems from immersing myself in the historicals of Harold Lamb and Robert E. Howard. Both men did an excellent job bringing their Muslim protagonists to life. Still, I can’t say it was especially careful deliberation that brought me to Baghdad—it just felt like the place Asim came from when he stalked out of my subconscious and started dictating his tales. Perhaps it all fell together when I realized that Haroun al-Rashid himself appeared in some of the Tales of the Arabian Nights.

Robert E. Howard, Harold Lamb, and Scheherazade—that sounds like three rich sources of literary inspiration. Could you tell us what about each compelled you? How you tried to emulate or adapt each?

Every adventure writer should spend some time studying the best of Robert E. Howard’s work. That man had an incredible narrative drive. And his prose is extremely vivid—he brings an entire scene to life with just a few phrases. He was so talented I could, and have, draft entire essays about his strengths as a writer, but I’ll just mention a few aspects that really impress me. For instance, I don’t know that anyone else has ever been capable of so clearly portraying the clash of entire armies as REH could, seamlessly moving his camera across the battle between knots of figures and important protagonists. When you write and edit all the time it’s hard not to turn off that “word architecture” part of your brain where you’re constantly analyzing the words. Howard’s one of the few authors whose work can still sweep me up so completely that I fall through the words and into the story. REH could craft lovely prose poetry when he wanted, but he knew when to sharpen focus and let the verbs do the heavy lifting. He was one of the best adventure writers we have, and I wish more fantasy writers would look deeper into his canon. Some of his lesser known stories are just as good, and even better, than the best of his Conan work. We’re fortunate that the recent Del Rey books have collected so much of it.

Harold Lamb didn’t have as much natural poetry in his soul as Robert E. Howard, but he was a fine craftsman with a natural cinematic pace who was far ahead of his contemporaries. He was also quite even-handed with most foreign cultures, writing without prejudice from the viewpoints of Mongols and Cossacks and Muslims and Hindus. All of that is laudable, but there’s more—he sent his characters into real world places so fantastic and unfamiliar to westerners that they might as well have been other planets. Like Howard, he could bring a strange setting to life with just a few choice phrases. Many of his protagonists were wily, and it is delightful to see Lamb back them into a corner and watch them think their way out with unexpected solutions. The fact that there’s almost always swordplay involved in those solutions make the stories all that much more exciting. Lamb was, simply, a writer of grand adventures, one who really should be studied by all adventure writers wanting to hone their craft, and celebrated by all those who love any flavor of heroic fiction.

When it comes to the Arabian Nights, I guess I was thrilled by what most of us have always enjoyed about them, the sheer joy of adventure, fantastic places, dark magics, the clash of blades, the flash of lovely eyes. As to emulation, I’ve worked hardest to understand how Howard and Lamb could swiftly paint settings and keep the story moving forward, and how they brought unfamiliar settings to life. I studied all three sources to see how they conjured images of glittering treasure, mighty foes, and places of wonder. I gave up long ago trying to sound exactly like any of the three of them, much as I’d like to be able to draft an action scene like Howard at his savage best.

Are there other novels that inspired this series? Perhaps in unexpected ways?

Well, the books I’ve read the most times are probably Leiber’s collection of Lankhmar stories, Swords Against Death, and Zelazny’s Amber books, although it’s been years since I’ve done so. While there are other Lankhmar stories I like just as well as those in Swords Against Death, I’ve always thought that particular volume had the strongest run of tales from the Lankhmar cycle. As a teenager I probably read it seven or eight times. I was just as devoted to Roger Zelazny’s first Chronicles of Amber. Five books sounds like a lot to re-read multiple times, but all of them together are probably the size of one modern fantasy paperback.

As a result, I can’t imagine that Leiber and Zelazny haven’t had a lasting influence upon me. I love the world building and pulp noir sensibilities of Leigh Brackett, queen of space opera, who was writing of Firefly-like characters twenty and thirty years before Han Solo every reached the silver screen. C. S. Forrester’s Hornblower stories were another favorite of mine, and later I fell under the spell of Jack Vance, Lord Dunsany, and Catherine Moore. All of these influenced me to greater or lesser extents, along with the original Star Trek, which I watched devotedly. I probably saw most of those episodes a dozen times. I loved the interaction between the central characters. In the best of episodes the dialogue brought them to life in a way I never really saw in the later series. Which reminds me; Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid is one of my very favorite movies. I love the interaction between the protagonists. I guess there’s a theme there….

Do you have a personal connection to the Arab world?

I can’t claim to have much contact with the Arab world save for immersion in old texts. I hope to return to my study of Arabic in the next year, but I have a few books to finish before I can pretend to have any spare time.

How did you go about researching this book? Eighth-century Baghdad seems like such a rich and complex area that it’d be hard to know where to start.

I’ve been a gamer since my junior high days, and as a result, when I first began my research I already owned two nifty source books set in the era, one from GURPS (Arabian Nights, by Phil Masters) and another from Iron Crown Enterprises (also titled Arabian Nights, by John Cambias). Non-role players might not know just how much information can be packed into a setting guide. A good one has to describe daily life, information about the culture and its religion, names, maps of famous places, etcetera.

These books were excellent starting points. When I really got serious I turned to John Howe’s translation of Andre Clot’s Harun al-Rashid and the World of the Thousand and One Arabian Nights, and to translations of writings from the period. The journals written by travelers and warriors were especially enlightening.

Have the current social and political dialogs regarding Islamic cultures affected how you’ve portrayed your characters and story?

Dabir and Asim have been seeing print for more than ten years in various short story venues, and they were not designed to be symbols of any particular political philosophy. They are brave and virtuous men from a culture some westerners fear and distrust, so I suppose by that fact alone I have ventured into the socio-political sphere. My intention is to tell adventure stories with compelling characters, not to lecture about morality, politics, or religion, but I suppose its inevitable that some of my own contentions will color my fiction—the simple one, say, that honorable folk can be found in the ancient middle-east.

Given that that many of your sources for inspiration come from American or European perceptions of eighth century Baghdad, when writing this book were you concerned with issues of cultural appropriation?

It’s certainly something to be alert for. I strive to create characters, not characitures, and to portray real cultures, not idealized or villified representations of them. One of the things I admire about Lamb was the way he showed heroes and villains on both sides of cultural divides; folk from different places were human, with flaws and virtues arising from their character and upbringing rather than because of the color of their skin. I follow Lamb’s lead and work very hard to show real people, not stereotypes. I would hope that my efforts keep me from the worst excesses of cultural appropriation. I am constantly trying to learn more so I can present the people and places with greater accuracy.

How would you say your career as an editor at Black Gate has helped shape you as an author?

That’s an interesting question. I suppose it’s gotten me to think about the starts to stories even more than I was already. I see a lot more beginnings than I do endings, to be honest. That’s just the way it works when you’re reading submissions. The biggest impact, though, probably comes from the number of people I’ve had the privilege to meet thanks to Black Gate’s John O’Neill. He’s the one who established the magazine—I didn’t come on board until issue #10. He’s opened up countless doors for me and has been extremely generous with his time and energy. I think my writing career would have had a much harder time getting launched without my work with the magazine and the Harold Lamb collections.

Huh, as a writer, I always find I’m a horrible editor; my desire to rewrite the story my way is always too strong. Do you find it difficult to switch authorial and editorial hats? Any tips for folks who are interested in both editing and writing?

Well, I was a professional editor for at least ten years before I ever joined the Black Gate staff, and that’s probably made it easier for me to switch hats. I cut my teeth editing all manner of computer books, from Idiot’s Guides to high level programming manuals (and no, I’m not particularly good with computers). To this day I still enjoy revising my work more than hammering out rough drafts. All those years playing with text, I’d guess. Tips—I suppose the best thing to do is to realize you shouldn’t attempt to make everyone sound the same. But then at Black Gate I work more as a developmental editor than a copy editor. If I like something and the pacing is off, I offer a few suggestions then toss it back to the writer rather than revising it heavily. I think that makes everyone happier, even if it sometimes takes multiple back and forth exchanges. I usually only do heavy revising with non-fiction, if I’m trying to help prop up some solid material from a less experienced writer. Anyone who’s submitting fiction needs to be able to fix the problems themselves. It’s just my job to point the way.

Howard Jones… hrmm… How often, if ever, are you—no doubt affectionately—nicknamed “HoJo?”

Almost never. I have one or two friends that occasionally refer to me that way in e-mail, but it doesn’t happen much, and I certainly haven’t encouraged it. I’ve never really had any nicknames. Only my father, one of my sisters, and an old friend (hey Gina!) ever managed to call me “Howie” without being irritating, so I’ve discouraged that as well. I just go by Howard. Two syllables; pretty easy to say.

Well, How-ard, thank you kindly for your time and the interview!

Heh. Thank you for your time and some questions that really got me thinking. I enjoyed myself.

Blake Charlton has had short stories published in several fantasy anthologies. Spellwright was his first novel. The sequel, Spellbound, is due out in Summer 2011.